Normally, there are real world repercussions to art being viewed as “timeless”, or “still relevant”. In 2020, I noticed an upswing in interest in one of my favorite movies, Spike Lee’s “Do The Right Thing”. What Mookie and company were discussing in the 1989 classic was somehow still relevant, and to many, the at-the-time thirty-one year old movie felt as if it could have been made now.

But pointing out exactly how strong “Do The Right Thing” remains in the 21st century reminds us of how little we’ve evolved as a society. There are still places like Sal’s that proudly refuse to place Black faces on the walls. There are still instigators like Buggin’ Out over-performing his rage. There is a new Radio Raheem every week. No one knows what the Right Thing is, but sometimes everyone is Mookke, grabbing that garbage can and flinging it into Sal’s window. Of course, the cops remain the cops. There might not be a way around that one.

I thought about this when an inmate in “Sing Sing” mentions YouTube. For some reason, I was under the impression Sing Sing had closed in the 1990’s, and the hostility of maximum security as seen in the movie emphasized the absence of technology. So I wondered, if it’s 1995 or so in this movie (which it’s not), why is someone mentioning YouTube? I immediately discarded the thought, because the conversation, and the settings, had remained the same over the decades. When people talk about the Prison Industrial Complex, they’re talking about something that has remained rigidly in place since the 90’s. Nothing has changed. It doesn’t matter if someone mentioned YouTube in prison in 1995 or 2015, because the nature of the conversation is exactly the same, the environment remains in place, and the captors are identical to who they were all those years ago. And every day remains the same for people in prison anyway. If “Sing Sing” still feels relevant in 2065, when YouTube is no more, we have failed as a society.

“Sing Sing” takes place in the titular institution, which is a Maximum Security Prison in New York. I don’t have a ton of reference points to this, because I was housed in a couple of low-security federal prisons, and this is a maximum security state facility. When you are convicted, you are given a classification score that determines where you will be housed. The higher your score, the higher your classification, and it is typically based on severity of the crime, your age and your priors. There is maximum security, medium security, low security (typically the most populous) and then minimum security (aka the camps). I once arrived at a maximum security institution via transfer, as I had to stay on layover for two weeks. Because inmates with different classification levels aren’t permitted to interact, I was kept in the SHU, given no recreation time in my own cell for days on end.

That being said, I didn’t see a security level that different in this film compared to what I experienced. “Sing Sing” doesn’t capture much interaction with guards, but what you see is brutal and dehumanizing (which is par for the course). Early in the film, inmates are forced to line up and stay still while guards yell at them, which is a fixture at every prison. Most of what you see in the movie is the pocket of safety one erects from the rest of this world. It is none too kind, but it is primarily a respite from the rest of the world of incarcerated people.

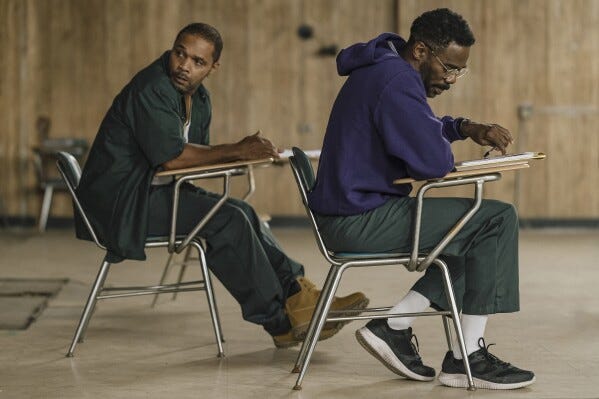

Early in the film, there is a shakedown between a veteran and what seems like a fish, the former played by Clarence “Divine Eyes” Maclin (as himself) and the latter by character actor Johnny Simmons (kudos to Simmons for participating in this very small role in a very small project). Maclin pressures the young newbie to owe him money out of a jailhouse lie, and the newbie reluctantly agrees out of terrified pressure, even though Maclin was inventing a tale in order to sell junk on the compound. I have seen those conversations, many times. A transaction borne out of a lie, necessary to avoid violence. I immediately felt bad for Simmons, before realizing this was just a movie. That being said, Simmons was getting a real life taste of what guys in prison experience regularly, even if it was just playacting.

The movie focuses on a theater program, largely being run by Divine G, played by Colman Domingo. This feels like an escape from the larger prison world, so in essence, the movie is about observing a bubble of safety within a cruel environment, as opposed to a look at that cruel world itself. I didn’t have such a luxury, we did not have a theater program of any sort. Though it doesn’t matter – the guards let you develop programs, and then just leave you alone, with no resources. When this group meets, it’s in an isolated room, with pencils and notebooks, and the helpful words of a volunteer (Paul Raci, excellent).

The closest I came to a program like this was when another inmate with directing experience wanted to put on his own play. I was recruited late, and we had weekly rehearsals in the Education building. Each week we would receive his directing on how to perform this material that he had written. And each week he would re-write and re-organize the play, revealing to us it was unfinished, no real beginning and no real end. After a while, it seemed clear the writer-director didn’t want to put on a play, as much as he wanted to direct us. I wrote a few scenes for him simply to speed up the process, but he remained in his own head, engaging in yelling matches when we didn’t hit our marks. He ended up in the SHU for disciplinary reasons before we could perform anything, and the piece faded away. No tears were shed.

“Sing Sing” is a strong film, but it is too close to me to attempt to “review”, per se. I could only sit in the moment, and let it take me away to a more difficult time. Which is partly why I felt irrational antagonism towards Domingo, who nonetheless performed a great courtesy by helping push this project into existence. I kept looking at him, a fine actor of several great movies, and thinking he was just a damned tourist. Here he was, in a movie with actual ex-cons reliving their experiences, and he was going home to steak tartare and, I’m not sure, a loving family? I don’t know his business. I hated him in this movie for this act of incarceration cosplay. Perhaps that’s a sign of how everything else in this movie so accurately recreates the feeling of incarceration. His performance is strong, likable, endearing. The man did nothing wrong. And I hated watching him in this. My apologies, Mr. Domingo. I hope this makes sense.

I was especially bothered by the narrative of his character. He has been fighting his case for a long time, fighting through (accurately-depicted) bureaucracy, because while you’re an inmate trying to prove your worth, they just don’t want to let you go. Think about that – you’re trying everything in your power to show that you don’t deserve to be treated like garbage, that you deserve a second chance, and the institution is just too bothered to have to go through the trouble of just opening the doors. Never forget, these men are prisoners.

In this case though, the movie was pursuing one of my least-favorite angles of media about incarceration – Divine G is chasing an elusive recording that will somehow exonerate him for his crime. Too often, when making movies and shows about the incarcerated, the narrative is pushed about the “innocent man” in prison, as if it doesn’t deserve to happen to this guy, this poor blameless man. Implicit in this argument is that it deserves to happen to someone. In spite of the need to tell stories about prison, there is the insistence that these stories are “chosen one” narratives, which is partly baked into the notion these stories need happy endings. Because that’s the key difference between my experiences and those of people in Sing Sing: in low security institutions, you’re likely going home eventually. But if you end up in Sing Sing, you’re probably there to the end.

The moments that struck me (troubled me, really) about the film were the times spent in the cell. Divine G has a two-man cell, but it’s cluttered, crowded and tiny. The lighting is dim, oppressive, unpleasant, the windows tinted. The bed, where you can lay flat, feels like the only moment you keep to yourself, and it is in a shared room. You see into other cells, and you see the listless manner in which officers collect an inmates belongings when they’re no longer there, walking among piles they’ve made of clothing and trinkets, seeing what needs to be fingered or grabbed. Usually it’s because they’ve been taken for disciplinary reasons. Sometimes it’s because they’re dead. They’re merely emptying the area for the next man. And the next. And the next.

I’m reminded of a time when I was teaching a film class and needed to borrow “Malcolm X” from the chapel. The chapel had religious films, primarily Christian (and cheap, and artless), but they offered fare for other religions too. Unfortunately, borrowing the film required a sit down with the chaplain, a devout Christian from the south who openly prayed during the Biden administration that Donald Trump would somehow be swept back into the presidency by an act of… I’d assume God?

When I asked for “Malcolm X”, he instead tried to convince me to pick something else to teach (as if I were teaching religion, and not film craft). He then began to bemoan Spike Lee’s films and, unprompted, asked me why would Mookie throw the garbage can into the window at Sal’s, what destroying Sal’s Pizzeria. This is the difficulty we experience in prison. We’re held captive to people who believe Sal’s Pizzeria must be protected.

Thank you for joining me on this bonus weekend edition, and thank you for frequenting the substack. I just wanted to give you some ICYMI action, and I’ll link to a few earlier entries you may find worth your while.

On how the public defines a crime, and also BONE TOMAHAWK.

How do halfway houses work? And also THE SQUARE.

My disturbed Stockholm Syndrome feelings about Dwayne Johnson, and BLACK ADAM.

When I did time with Paul Manafort, and also TEEN TITANS GO TO THE MOVIES.

Fathers and sons in prison, and the exceptional ALL DAY AND A NIGHT.

The intersection where Martin Shkreli and I meet, and PHARMA BRO.

What does innocence mean to the public? And THE IRISHMAN.

How the COVID lockdown was botched in prison, and CARTER.

Thanks for reading.

I really enjoyed this, watched it last night. Very touching. I took the video footage as a condemnation of the magic bullet so to speak. It didn't change anything for him.

Also, really cool to hear how they split the revenue from the film.

I’ve been on the fence about watching Sing Sing. I’m wary of its vibe: great performances in the service of manipulative wish-fulfilment, and a feeling that it’s depicting lives that I’m only familiar with from other movies. But I’ll get to it at some point.