How do you square a general disinterest in animation, but an appreciation for Marvel programming? Marvel shows and movies are escapist fare centered on one-dimensional conflicts between characters that can never exist. How is it that different from a less-demanding ‘toon? This is to say, never mind those movies’ excessive over-reliance on CGI, resulting in entire sequences that are computer-generated and very much examples of animation. We didn’t watch animation in prison, and yet those in control of the remote were all about superhero fare. At the time when those two interests met, specifically in showings of the Oscar-winning “Spider-Man: Into The Spiderverse”, the group was all-in on animated superheroics.

“Big Hero 6”, which is also an animated Oscar-winning Marvel effort, wasn’t something we watched, and indeed it’s weaker fare featuring significantly less-familiar characters. This is set in a technologically-advanced future, and it wasn’t recognizably any Marvel future of which I was familiar (so no 2099 vibes, bummer). San Franstokyo is the setting, and it sounds like the comic team has ties to the larger Marvel world that have been severed for this adventure. For all intents and purposes, this is something of an original creation to most of us, which is a nice flavor from Disney, typically too dependent on their consistent brands and franchises. Of course, this movie has since spawned a couple of television series’, so I suppose it is now one of those brands.

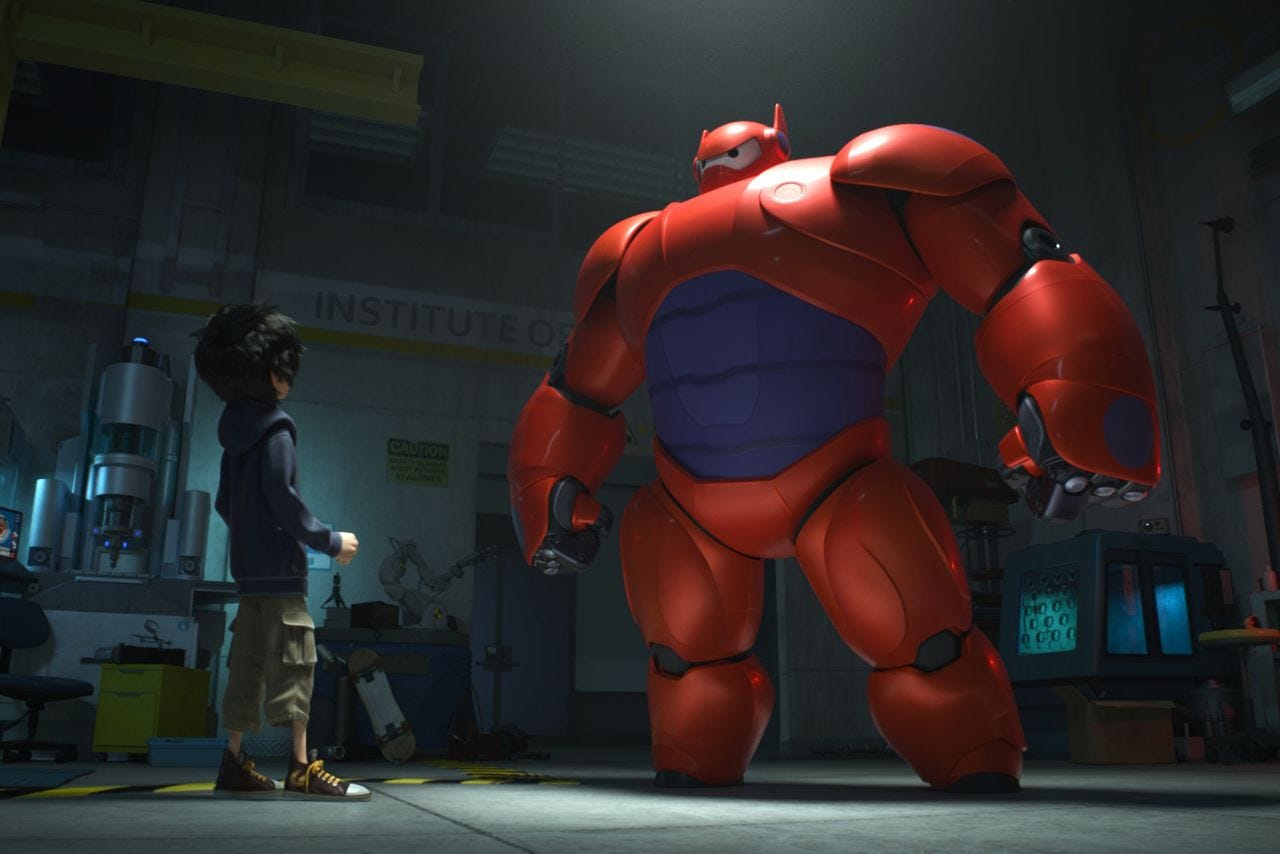

The story follows a teenage boy named Hiro who is pushed into a group of similarly-gifted science nerds by his supportive older brother Tadashi. Hiro’s interests lie in robotics, and he specializes in tiny nanobots that form anything the user might desire, something that may become relevant to the plot later. But not in the first act, when a supposedly “accidental” explosion takes Tadashi’s life. Left behind by Tadashi is Baymax, a cuddly (and fairly toyetic) robot who is bouncy, curvy and generally kind of adorable. It’s one of the movie’s contrivances that this bot was created to provide healthcare, but can also be reprogrammed to fulfill any and all action movie needs.

This comes in handy as Hiro bands with his new science friend nerds. Not only is the mystery of Tadashi’s death unsolved, but Hiro has found out someone is using his nanobots, which he figured were also lost in the fire. The conspiracy leads to a cool-suited supervillain with a mystery identity, and a lot of suspects. Cue big action sequences, animated stunts, and reversals as to whether the heroes or villains are winning, while Hiro bonds with his new buddies (and then doesn’t, and then does again).

Hiro isn’t exactly one of Disney’s timeless characterizations, and most of the storyline sees him being reactive to the various plot developments. There’s also the repeated instances of Hiro hiding his robot from others, not helped by the fact that the walking contraption is seemingly still in beta stage. This is the sort of stuff that can be overdone, and while Disney here is employing high level writers and animators to make Baymax a memorable sight gag, there is a sense they’re going to run every variation of his supposed incompetence into the ground. Of the cowriters, Dan Gerson was a scribe who had contributed to a number of Pixar films thus far (as had co-directors Don Hall and Chris Williams), while Jordan Roberts previously wrote and directed “3,2,1, Frankie Go Boom”, an obnoxious comedy that seemed filled with familiar indie movie tropes. These are guys who know formula, in other words, perhaps to the movie’s detriment.

There’s a conversation started, but not articulated, about productive and beneficial technology versus militarized, violent use. This manifests in Baymax, who becomes quite violent when reprogrammed instead of the slapstick-y healing robot he’s built to be. The villains’ ultimate motivation seems to be rationalized by the idea that you create devices for capitalism, and you cannot be responsible for what happens to your gizmos while you’re merely trying to put a roof over your head. Again, young Hiro would be a good example as to being a character that embodies some sort of moral here, but the movie doesn’t have a lot of time for that. And, in true superhero fashion, the characters are, by film’s end, definitively a superhero team, though their scientific interests manifest in predictable violence and fisticuffs. Look out for a voice cameo by Stan Lee. And, amusingly, another voice cameo by the soon-to-be-relevant Billy Bush as a newscaster.

I wanted to address something that came to light as I was writing this (which, in no way, seals with “Big Hero 6”, so if you were looking for some Disney-related prison talk, I must disappoint). Even being in the belly of the beast for several years, I’m still learning about the Bureau Of Prisons. And just recently, via this excellent article from The Appeal, I have learned of CMU’s, which stand for a Communication Management Unit. A great name considering the purpose – this is yet another apparatus within the prison system to silence inmates.

This is what’s important to know about reporting you may read about the prison system. If there is cruelty being done to inmates, the only way you’d find out is from information sourced from the inmates themselves. There are so many prisons, state and federal, nationwide, and it is impossible for there to be a watchdog system in place. And what happens if an inmate can’t communicate with the outside world, can’t call, can’t email, can’t write letters? Who would know of abuse? It’s hard enough getting people to care about conditions in prison. What if they never found out?

It’s a two-step process to reach out to the media about what goes on behind closed doors, the first step involving communication and the second geared towards making media people want to cover the issue. In my earlier days in county, there was a summer where we went two whole months in our cells with no recreation. The prison claimed it was a “staffing” issue, but the fact is certain people had moved on, and were not replaced, and money was being saved during the hottest months. Legally, recreation is required, and those cells were infamously tiny, maybe 14-by-8. My family reached out to media, and were told it wasn’t enough of a hook to report on the issue – they needed to hear from multiple family members before they reported on the issue.

CMU’s take that out of the equation. If approval was ever sought for certain B.O.P. activities, it’s likely the federal government would approve, due to “the penological goals of the institution”, a common blanket phrase used to describe literally any decision made. In this case, the excuse is that a CMU houses terrorists, and terrorists apparently should have less rights than regular criminals, and also a “terrorist” is whomever the Justice Department calls a terrorist. No criteria needed, apparently. In this case, it is meant to be a quirk and/or coincidence that 70% of the inmates in CMU’s are Muslim while Muslims make up only 6% of the federal prison system overall. Most of what I write concerns only people who might willingly break the law. But it’s important to note articles like this, which explain how any American could be categorized not only as criminal, but as terrorist.

A BRIEF EDIT:

In this entry I wrote a couple of weeks back, I was detailing the best movies I saw when I was down, which I will therefore not write about on this site (probably not). I neglected two:

“Bushwick”, a low-budget single-take action thriller depicting the eruption of a civil war as seen from Brooklyn. A great John Carpenter vibe and a solid performance from Dave Bautista. I’d rank it Top Ten on that list.

And “The 24th”, Ava DuVernay’s Netflix documentary about the history of modern incarceration. Obviously, I’d highly recommend.