We’ve got a week of real heavy hitters, which means I’ve gotta address the bold debut of Ari Aster. “Hereditary” is the one title I see mentioned from this particular era of films (‘14-’23) that stands out as a horror lodestar. When people talk about “elevated horror”, when they say that all horror movies are centered on “trauma”, it sounds like “Hereditary” is the one they are recalling. Jordan Peele’s “Get Out” (which I saw in prison many times) was the box office and critics’ favorite of this period, helping usher in this Golden Age Of Horror. But I kept hearing about “Hereditary” as the raw, underground equivalent. My mother told me about seeing “Get Out”. My mother could probably not withstand “Hereditary”.

I have since seen Aster’s other movies, so I think I get what he’s about, for the most part. Aster’s “Beau Is Afraid” was one of the first movies I saw in the theater as a free man, and it gave me plenty to digest, even if it peaks extremely early and then slowly slides downhill for the remaining couple (!) of hours – I could talk about it plenty more, but I don’t want to sidetrack this convo too much. I will say, however, that it’s probably best I didn’t see “Hereditary” in the theater. Surely I would have had to get up and pace a few times.

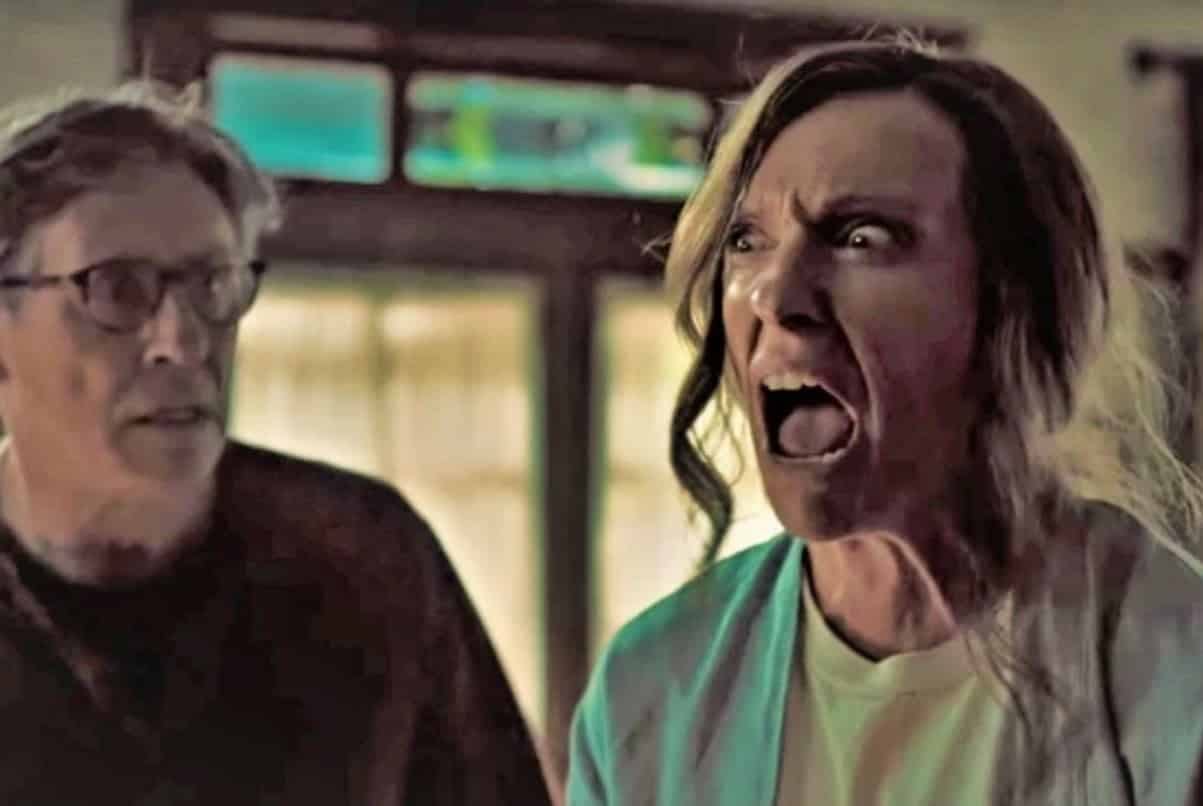

There is a family shattered at the start of “Hereditary”. An elderly mother has died, and the family has united. But who are these unfamiliar people at the funeral? The excellent Toni Collette, as Annie, isn’t relieved to know her mother’s life was fuller than she had thought. Instead, it is unsettling. Each unfamiliar person is like a door slightly left ajar. Annie reacts to this with a jaundiced eye, but it seems as if she has no chance to really process the secrets her mother left behind. She instead is still expected to be a mother. One of the film’s many themes seems to be the refusal to allow a mother to be anything other than maternal. This gendered hostility can be seen in her passive-aggressive husband Steve (Gabriel Byrne), who comfortably slips between spouse and therapist to diagnose, and ultimately minimalize, his wife.

Which doesn’t let any other member of the family off the hook. In particular, young Alex Wolff is the family’s son Peter, and it’s a performance that sweats through the screen. Initially, he seems like just another moody teen, with his ratty little secrets hoarded away and hidden from view, and his own hormonal insecurities blindly puppeteering his still-developing body. Soon, however, he feels like the conduit for the family curse that is discussed in ironically hushed tones. What comes across is that, more significantly, Peter is entirely under-equipped to handle any real world problems headed his way, never mind an actual family curse.

And then there’s young Charlie, their developmentally disabled sweetheart of a preteen daughter. I have to confess something – I feel ill-equipped to emotionally function when it comes to the disabled. My heart breaks for them so much, and I just feel powerless against the world, I feel like I have nothing to offer them. I freeze when I try to consider how difficult life must be for them, and what they may register compared to what does not occur to them. This poor little girl is so pivotal to the film’s first act. And then what happens to her… I wished I had a cigarette, It’s one of the most crippling moments in any movie for me. It is by now an infamous cinematic moment, I know, a slice of ghoulish black humor for many. I am not offended. But for whatever pleasures that moment and its aftermath have for horror fans, they do not exist for me. I suppose horror movies are about discovering your limits. Very well, then.

I’ve heard some argument about the resolution of this film. Early on, there’s a suggestion regarding a Satanic cult (an interest Ari Aster would pursue in “Midsommar”), but when it is revisited for the Third Act it feels somewhat inorganic. A storytelling gamble that doesn’t pay off, perhaps? This feels like a movie about a family curse (hence the title), so anything that distracts from that, no matter how strong, will feel like a distraction. On a very basic level, it does mean that we have zero expectations for the narrative’s close. I’ll give credit to Aster and company, because that approach worked tremendously for me.

As I have mentioned before, I wanted to start this substack because I noticed America was now in a position to ask itself what it meant to be a criminal, to be a felon. Criminal records weigh down a considerable amount of Americans, a great deal more than you’d think. Consider how 33% of African-American males have a criminal record, and how many of them have to live with that stigma, culturally, socially, professionally. That status would keep them from obtaining housing, jobs. It hasn’t stopped a certain white man from campaigning for the most important job in America. He’s derided his competitor by claiming she had never held down a part-time job at McDonald’s as she had claimed. I wonder if McDonald’s would hire someone guilty on 34 counts who was also found liable for rape in a civil case. Maybe not at the front counter.

It’s people like that who force the question as to who we, as a public, should consider a criminal. I’ve seen a movement in some media to call Missouri Governor Mike Parson a murderer, and this is something I fully endorse. Parson did not commit the murder by his own hand necessarily – all politicians know how to keep their own hands clean. But Governor Parson knew that Marcellus Williams was a wrongfully convicted, and instead of granting the man his freedom, he kept him on Death Row, allowing for his recent execution. I’ll go ahead and say the death penalty is a sickening policy, and we have used the guilt of some men to justify murder. But what do we call a person who allows for the killing of an innocent man? That’s correct, that would be a murderer. Parson reportedly has no record of providing clemency for anyone on death row, so in this case he appears to be a serial murderer. Mike Parson is a man who keeps the trains running on time.

Mostly. Because as Robyn Pennacchia at Wonkette points out, Parson did indeed pardon two people you may recognize. Mark and Patricia McCloskey, a wealthy white couple, were found guilty of fourth degree assault and second degree harassment for brandishing firearms towards racial justice protesters walking down their street. Mike Parson did not feel the need to legally intervene when an innocent man was about to be killed. He did feel the need to interfere when two privileged white people faced legal ramifications from actions in which they engaged on camera.

This is not about innocence and guilt, however. This is about murder. We should utilize the death penalty, full stop. In any other walk of life, no matter who someone is, if you have a chance to save them from certain death, you would do so and seek rationalization later. Instead, Parson murdered a man, an innocent man, and pardoned guilty people. He would probably think it best you didn’t acknowledge that the dead man was Black, and the living white. Perhaps it’s just a coincidence.

I found Hereditary brilliant, and very hard to watch. I’ve never seen anything quite like it, and in fact would be hard pressed to write or even talk about it. Another good piece; the details about the governor are tough to stomach.

If I may drop my own thoughts on the film here for your perusal… 😜

https://open.substack.com/pub/jackandersonkeane/p/the-hopelessness-and-horror-of-hereditary-8f1353809078?r=1lzok0&utm_medium=ios